Metadata has been positioned as the thing that will save SharePoint for as long as I can remember.

“If we just tag things properly, search will work.”

“If we just design the right columns, folders will disappear.”

“If we just enforce metadata, users will adapt.”

Multiple iterations of the platform later, and none of the above proved to be entirely true.

Metadata is not inherently good or bad. It is only as useful as people are willing to apply it. And that is where most implementations fall apart.

I have seen metadata models that looked incredible on a whiteboard. Perfectly normalized. Carefully named. Aligned with every business unit. And completely ignored the moment they hit a document library.

The fastest way to make metadata fail is to design it without watching how people actually work.

Required fields are a great example. On paper, they guarantee consistency. In reality, they guarantee frustration. Users rush through uploads, pick the first option in every dropdown, and move on. The data exists, but it is meaningless.

That is not user failure. That is design failure.

Managed metadata makes this even more obvious. Term sets promise consistency and reuse, but when they grow unchecked or are designed far away from real work, they become intimidating. Microsoft has long positioned managed metadata as a way to standardize classification, but standardization only works when terms are understandable and stable.

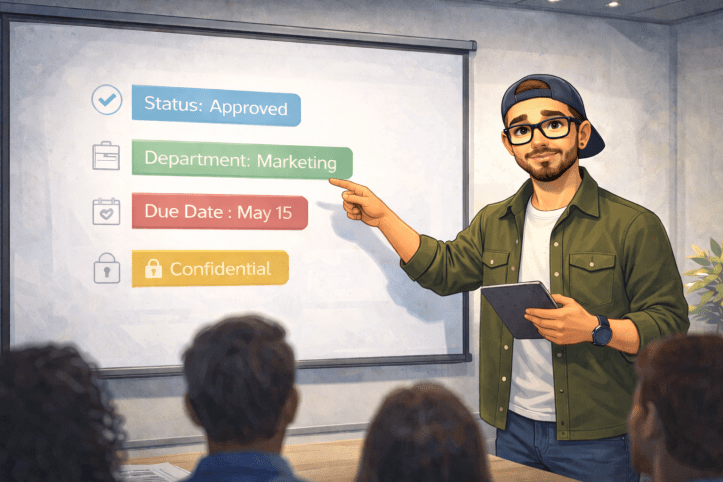

Good metadata answers questions users already have, what this is, who it is for, what state it is in, and whether it can be trusted.

Bad metadata answers questions no one is asking.

Another common mistake is overloading a single library with metadata meant to serve every possible scenario. One library. Fifteen columns. Ten content types. Endless views. At that point, metadata is not helping. It is punishing.

Metadata works best when it is boring.

A small number of columns. Clear names. Limited choices. Defaults where possible. Metadata that changes rarely and means something when it does.

This is also where ownership matters. If no one owns the metadata model, it will drift. Terms lose meaning. New values get added without context. Suddenly two tags mean the same thing and no one knows which one to use. Microsoft calls this out indirectly in their guidance on information architecture in modern SharePoint, but it often gets overlooked.

When metadata is owned, reviewed, and occasionally pruned, it stays useful. When it is set once and forgotten, it becomes noise.

This is also where I am cautiously optimistic about the future.

Features like auto-apply metadata and column defaults are finally shifting the burden away from users. And with AI entering the picture, we are starting to see a world where metadata can be suggested, inferred, or filled automatically based on content, not clicks.

That is the right direction.

Metadata should be something users benefit from, not something they are forced to maintain. If AI can help tag content consistently and invisibly, metadata might finally deliver on the promise it has always made.

The goal of metadata is not to impress architects. The goal is to help users find the right thing faster, without thinking about SharePoint at all.

If users are not using your metadata, the answer is not more training. It is better design, better defaults, and less manual effort.

Metadata that only works in theory rarely works in practice, and it almost never shows up in search the way you expect it to.

This post is part of my 25 days of SharePoint series, created to celebrate SharePoint’s 25th anniversary and lead up to the SharePoint at 25 digital event on March 2.

Each post reflects on what actually made SharePoint last 25 years, the wins, the mistakes, and the lessons learned from building, breaking, and rebuilding it in real organizations.

You can find all posts in this series here.

If there’s a topic you think I should cover next, a SharePoint mistake you keep seeing, or a question no one ever answers straight, leave a comment. This series is shaped by real experiences, not marketing slides.